French Language Requirements at Work in Canada

The linguistic landscape of Canadian workplaces is shaped by the country's bilingual character and regional language laws. English and French are Canada’s official languages at the federal level, but nowhere are language requirements more prominent than in the province of Quebec. In Quebec, French is not only the predominant language of daily life but is legally protected as the “normal and usual language of work”. At the same time, other provinces and the federal government have their own policies on bilingualism. This article provides a comprehensive look at French language requirements in the workplace – covering Quebec’s strict language laws, federal bilingualism rules, practices in other provinces, sector-specific variations, and practical advice for newcomers integrating into the workforce.

In Montreal and across Quebec, French is prioritized on public signage and in workplaces. For example, some stop signs display both “arrêt” (French for stop) and “stop,” reflecting Quebec’s French-first language laws while acknowledging the presence of English.

Quebec’s French Language Workplace Laws

Quebec has unique and robust laws to ensure French is the dominant language in workplaces. The backbone is the Charter of the French Language, commonly known as Bill 101, first enacted in 1977. Bill 101 declared French the official language of Quebec and mandated French as the primary language of work, business, education, and government in the province. Over the years, the Charter has been strengthened, most recently by Bill 96 (adopted in 2022), which introduced new requirements for employers to reinforce the use of French in professional settings.

French as the Normal Language of Work: Under these laws, employers must operate in French and employees have the right to carry out their work in French. The Office québécois de la langue française (OQLF), Quebec’s language watchdog, emphasizes that its mission is to ensure “French is the normal and usual language of work, communications, commerce, [and] business” in Quebec. In practice, this means French should be used in internal communications, workplace documents, and customer service as the default language. English or other languages can be used, but French must remain preeminent in visibility and usage.

Key Obligations for Quebec Employers

Quebec’s Charter of the French Language imposes several legal obligations on employers to maintain French in the workplace. Violating these rules can lead to complaints, inspections, and hefty penalties. Here are the major requirements:

Job Postings and Hiring: Employers must produce job postings in French (they can be bilingual, but French must be equally prominent). If an employer also advertises a position in another language, the French version of the ad must appear simultaneously and reach an audience of comparable size. Crucially, if a position requires knowledge of a language other than French (for example, requiring English fluency), the employer must explicitly justify this requirement in the job posting. The law mandates a rigorous analysis before imposing such a requirement: the employer must take all reasonable steps to avoid needing another language, assess the true linguistic needs of the role, and ensure no current staff could fulfill those needs. Only if those conditions are met can another language be listed as required, and the posting must state the reasons why that additional language is needed. In short, an employer cannot casually add “bilingual required” to a job ad in Quebec – they must demonstrate that English (or another language) is genuinely necessary for the work.

Right to Work in French: Employees (and job candidates) have the right to carry out their work in French. An employer cannot refuse to hire, promote, or retain someone solely because they lack knowledge of a language other than French, unless the nature of the job truly demands it. The Charter explicitly prohibits requiring knowledge of any language besides French as a condition of employment, unless the tasks of the position absolutely require it and the employer has first taken all reasonable measures to avoid imposing that requirement. This provision was strengthened by Bill 96. For example, in a recent case, a Quebec administrative tribunal upheld a complaint by a man who was asked to submit his resume in English and do an interview in a third language for a job – the tribunal found the employer failed to prove that those language requirements were necessary or that they had tried to avoid them. This case demonstrates how employees can invoke their right to work in French and challenge employers who overstep the language rules.

Workplace Communications and Documents: Employers must provide virtually all written communications and documentation to employees in French. This includes offer letters, employment contracts, collective agreements, employee handbooks, policies (like anti-harassment or health and safety policies), training materials, and internal memos or emails intended for staff broadly. These documents can be bilingual or translated, but the French version must be at least as accessible and of equal quality as any other language version. In practice, many companies provide both French and English versions of certain documents, but they cannot give an English document without a French equivalent unless an employee specifically requests the English. Offers of promotion or transfer must also be in French. Software and tools used for work (like user interfaces of computer programs) should be available in French versions if such exist – employees can demand French-language software or work tools when available.

Oral Communication: While the law is stringent about written materials, it does not outright ban employees from speaking other languages on the job in informal settings. Colleagues are generally free to converse in any language between themselves unless the company is under specific “francization” rules (more on that below) that mandate French usage. However, an employer cannot prohibit an employee from speaking French or harass them for using French. In contrast, an employer could request employees to speak French during official meetings or when serving customers, as part of ensuring French as the language of business. The bottom line is that employees cannot be penalized or discriminated against for speaking French, nor for not knowing English. Quebec law even created a new protection in 2022: the right to a workplace free of harassment or discrimination related to language – meaning no teasing, exclusion, or punitive measures because someone speaks French or isn’t fluent in another language.

Customer Service and Signage: In consumer-facing businesses (retail, hospitality, etc.), customers have the right to be served in French. Employers must ensure there is always at least one French-speaking staff member on duty to assist customers in French at all times. Store signs, product labels, menus, and public-facing information must be in French (or bilingual with French prominent). Trademarks and certain exceptions aside, French text must be “markedly predominant” on signs if another language is present. Companies have been fined for offenses like having an English-only website or English-only signs in Quebec. For example, a popular popcorn chain was fined $2,500 by the OQLF because its website for a Quebec location had no French version at all, violating the rule that commercial publications (including websites) must be in French. (The company swiftly updated its site to be bilingual after the fine.) This enforcement underscores how seriously Quebec takes French in all outward-facing aspects of business.

Francization of the Workplace: Larger businesses in Quebec are subject to a process called francization, which is overseen by the OQLF. Traditionally, companies with 50 or more employees had to register with the OQLF and undergo an assessment of their linguistic situation. They would receive a francization certificate once the OQLF was satisfied that French was “generalized at all levels” of the company. If not, the company had to implement a francization program (an action plan to increase French usage, e.g. translating software, offering French classes to staff, changing product packaging to French). Bill 96 lowered the threshold – now any business with 25 or more employees in Quebec for a 6-month period must register with the OQLF and embark on the francization process. As of June 1, 2025, thousands of mid-size companies (25–49 employees) are newly required to comply. Such businesses must submit a report on the status of French in their operations and may be required to make adjustments. In practical terms, if you work for a company of that size in Quebec, don’t be surprised if your employer starts rolling out more French tools or terminology policies to meet OQLF standards. The goal is to ensure even medium workplaces adhere to the spirit of making French the common language at work.

Enforcement and Consequences in Quebec

Quebec’s language laws have real teeth. The OQLF has powers to investigate workplaces proactively or in response to complaints. If a worker, customer, or even an applicant believes an employer isn’t following the rules – say a job ad seemed to demand unjustified English, or an employee manual is only in English – they can file a complaint and trigger an OQLF inquiry. The OQLF can inspect premises, question employers, and request documents to check compliance. Often, the OQLF will first issue a warning and give the employer a deadline to rectify the situation (for example, translate the website or add French signage).

Failure to comply can lead to penal fines. Fines were stiffened under Bill 96 and can range from $3,000 up to $30,000 per day of an offense in the case of serious infractions. Repeat offenders face double or triple fines. In extreme cases, the government can even suspend or revoke permits or licenses of a business that persistently flouts language laws (though this is rare). The list of recent fines issued by the OQLF includes companies of all kinds – from retail chains to restaurants – who had signage or websites not in compliance. For instance, aside from the popcorn website case, a Montreal grocery store and a restaurant chain were fined around $1,500 each for posting exterior signs or menus where English text was more prominent than French. These examples serve as reminders that in Quebec’s business environment, ignoring French can be costly.

It’s not just the OQLF – employees themselves have recourse if they feel their language rights are violated at work. Quebec’s labour standards board (CNESST) can take up complaints against employers who, for example, punish an employee for speaking French or for not speaking English. Reprisals, harassment, or discriminatory practices related to language can lead to legal proceedings at the Administrative Labour Tribunal, with CNESST support. The newly decided case of the man asked to interview in Korean (mentioned above) illustrates how the tribunal applies these rules under Bill 96: it upheld the worker’s complaint and is considering remedies for him. This climate empowers workers in Quebec to insist on their French language rights without fear.

Overall, Quebec’s strict regime means that both employers and employees must be mindful: Employers need to weave French into the fabric of the workplace in good faith, and employees can expect to work in French by default. However, this doesn’t mean other languages vanish from Quebec workplaces – rather, the law creates a framework where French is foundational, and other languages play a supporting role only where truly necessary or as a courtesy.

Official Bilingualism in Federal Workplaces

Outside of Quebec’s provincial jurisdiction, Canada’s federal government has its own set of language requirements which differ in scope and intent. The federal rules are about ensuring services and employment opportunities in both official languages (English and French) across Canada, reflecting the country’s bilingual nature. The key law here is the Official Languages Act (OLA), a federal statute that applies to federal institutions (government departments, agencies, Crown corporations, etc.).

Under the Official Languages Act, English and French are recognized as having equal status in the Government of Canada. For the workplace, this translates into specific rights for federal public servants. In designated bilingual regions – notably the National Capital Region (Ottawa–Gatineau), Montreal, and New Brunswick, among others – federal employees have the right to work in the official language of their choice. For example, a federal employee in a Montreal-based office or in Ottawa can generally choose to correspond, draft documents, and converse with colleagues in either English or French, and the employer must accommodate that. Meetings might be bilingual or with translation, documents are often issued in both languages, and supervisors in bilingual areas are expected to be able to communicate with staff in both languages. In regions not designated bilingual, the “language of work” is typically the majority language (for instance, in a federal office in Vancouver, the working language is English, whereas in a federal office in rural Quebec, it’s French). However, even in those “unilingual” regions, employees can often get support or key materials in the other language if they need, and importantly, any services to the public must still be provided in both languages where there is demand.

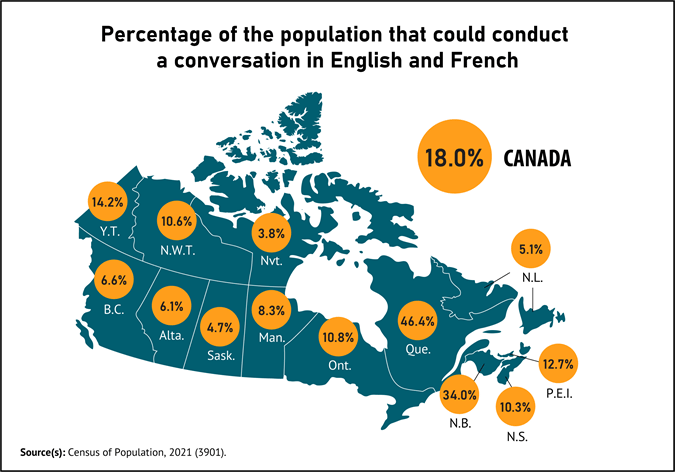

To implement these rights, the federal public service designates many positions as bilingual. According to recent data, around 42% of federal public service positions are officially designated bilingual. This means that to be hired for those jobs, a person must meet language proficiency requirements in both English and French (typically tested and rated as levels for reading, writing, speaking). Positions that interact with the public or that are located in bilingual regions are frequently bilingual imperative. Others are unilingual (English essential or French essential), meaning only one language is required. Notably, all services to the Canadian public by federal institutions are guaranteed in both languages wherever significant demand exists, and federal courts and Parliament operate in both languages.

Within the public service work environment, federal policy goes even further: certain roles, especially management and supervisory positions in bilingual regions, must be staffed by bilingual individuals. This ensures that if a manager has a mix of English-speaking and French-speaking employees, each employee can be supervised in their preferred official language. For example, a director in a federal department in Montreal would be expected to conduct team meetings in both languages or ensure translation, and to write emails or performance reviews in the employee’s official language of choice. This has practical implications for careers: to rise into the executive ranks of the federal service, one almost always needs to be fluent in both languages. In fact, many federal workers take government-provided language training to attain the bilingual levels required for promotion. The government supports this with language classes and even offers a “bilingualism bonus” – an annual $800 bonus for employees who occupy bilingual positions and meet the language requirements.

Despite these robust policies, it’s important to note that federal language requirements apply only to federal institutions and services, not to private companies (except those private entities that fall under federal regulation in certain sectors might have some obligations to serve the public in both languages). So, if you work for a federal agency or want a job in one, bilingualism is a significant factor. By contrast, if you work for a private company in, say, Ontario or British Columbia, the Official Languages Act doesn’t directly impose requirements on your employer – unless your job is to liaise with the federal government or serve customers nationwide.

In summary, the federal workplace is governed by principles of bilingual accommodation and service. The emphasis is on employee rights and public service: employees can use English or French (in designated areas), and the public can expect service in either language. The federal approach is more about balance and choice, rather than declaring one language to dominate the other. This differs from Quebec’s approach, which is about elevating French above English in that province. For employees, if you aim for a federal public service career, developing strong skills in both official languages is extremely valuable – not only to access a wider range of positions (since roughly two in five positions require it) but also to better serve a bilingual public.

French Language Requirements in Other Provinces

Outside Quebec, no other province mandates French as the primary workplace language in the private sector. English is the predominant working language in most provinces. However, some provinces have significant French-speaking populations and official policies to provide services in French, which in turn create employment requirements for bilingual staff in certain roles. Let’s look at key regions:

New Brunswick: Uniquely, New Brunswick is the only officially bilingual province in Canada. Both English and French have equal status under provincial law and the Canadian Constitution in New Brunswick. The provincial Official Languages Act of New Brunswick guarantees citizens the right to receive all provincial government services in the language of their choice (English or French). This means that provincial government departments, courts, hospitals, police services, and even many municipalities in New Brunswick must provide services in both languages. For example, a New Brunswicker can walk into any Service New Brunswick office or call a government line and expect to be served in their preferred language. To fulfill this, a large proportion of public sector jobs in N.B. are designated bilingual. Many provincial civil servants, nurses, police officers, etc., in New Brunswick must be able to speak both French and English. Even when a government institution in N.B. doesn’t require every employee to be bilingual, it must ensure that the team as a whole can serve the public in both languages, often through an “active offer” (greeting and signaling that service is available in either language). For employees, this environment means French proficiency is a significant asset and often a requirement for public-facing or higher-level roles. The emphasis, however, is on service to the public; internally, a New Brunswick government office might operate mostly in the language of the majority of its employees in that region, but any given employee is typically entitled to use either English or French in dealings with the provincial government as an employer too (mirroring federal policy). Outside the government, New Brunswick’s private sector will cater to the bilingual nature of the market – e.g. banks, retail stores, and businesses in areas with many francophone customers often seek bilingual staff. It’s common to see job postings in N.B. noting “bilingual (FR/EN) required or an asset,” because businesses want to serve the entire market. In short, New Brunswick’s labor market, especially in public service, has the highest demand for bilingual workers in Canada outside of federal institutions.

Ontario: Ontario is not officially bilingual province-wide, but it has a large French-speaking minority (Franco-Ontarians, about half a million people). Ontario’s French Language Services Act (FLSA) requires the provincial government to provide French-language services in regions where there is a significant francophone population. In practice, Ontario has designated 26 regions (largely in eastern, northeastern, and central Ontario) where ministries and agencies must offer services in French to the public. This covers government offices like health services, social services, courts, etc., in places like Ottawa, Sudbury, Toronto (for provincial services), and so on. It also covers certain public institutions that opt into designation (for example, some hospitals, school boards, or in the cited case the University of Ottawa, have special designation under FLSA to guarantee services and programs in French). For job-seekers, this means some Ontario public service jobs require French – if you’re applying to be a clerk at a ServiceOntario center in a designated bilingual area, or a police officer in Ottawa, or a nurse in a designated bilingual hospital, you may need to be bilingual to be hired. However, many other positions are English-only, especially in non-designated areas. Ontario’s private businesses have no legal obligation to operate in French, except in industries like consumer packaging or labeling where federal laws apply. Nonetheless, in cities like Ottawa or communities in Northern Ontario with many French speakers, private employers (from banks to call centers) often prefer or require bilingual staff to serve customers. For instance, a sales job in Ottawa may list French as an asset since the company doesn’t want to turn away francophone clients. Culturally, Ontario businesses view bilingualism as a market-driven asset rather than a legal mandate. Thus, French skills can enhance employability and customer service reach but are not universally mandated by law as in Quebec.

Manitoba: Manitoba has historical bilingual roots (stemming from the Manitoba Act of 1870 which made the Legislature and laws bilingual). Today, Manitoba’s laws guarantee the right to use French in the courts and to receive certain services in French, especially in designated “bilingual service centers” regions. The province has a policy (though not as sweeping as N.B. or Ontario’s law) to offer French services in areas with significant francophone population (e.g., Saint-Boniface in Winnipeg or some rural communities). Provincial employees in those service roles need to be bilingual, but generally English is the main language of work in Manitoba’s government and certainly in private industry. There is a French-language Services Secretariat and some requirements for government forms and websites to be bilingual. So, while Manitoba is officially bilingual in its legislature and courts, in daily work life the requirement to know French is limited to specific roles (like certain health, social service, or administrative jobs that serve francophone clients).

Other Provinces and Territories: Most other provinces (British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, etc.) and territories are overwhelmingly English-speaking in the workplace. They do not have provincial laws requiring French in workplaces or services (aside from providing French schooling and some basic services to French minorities). That said, even in these regions, certain sectors might seek bilingual talent. For example, a tourism office in Banff, Alberta might want a French-speaking guide to help Quebec tourists; a national company’s call center in Winnipeg might require some bilingual agents to handle calls from Quebec; or an airline based in Calgary will require flight attendants to make announcements in both languages and serve passengers in both. These are not local legal requirements, but rather business decisions driven by Canada’s national bilingual context. The federal government’s presence in every province also means there are federal jobs everywhere that may require French. For example, a federal agency regional office in Regina might designate some bilingual positions if it serves the public or has a bilingual work unit.

In summary, outside Quebec, French language requirements at work are primarily about ensuring service to the public in French where needed, rather than making French the internal working language. New Brunswick stands out as fully bilingual, affecting many jobs. Ontario and Manitoba have significant bilingual service requirements in pockets, affecting some jobs. Elsewhere, French is more of an asset than a requirement, except in federal roles. However, it’s worth noting that across English Canada, attitudes toward bilingual hiring can vary – some employers enthusiastically seek bilingual hires to broaden their market and because it looks good to have bilingual staff; others might not consider it at all if their business doesn’t touch any francophone clientele.

For newcomers or workers relocating in Canada outside Quebec: if you already speak French, you might find extra opportunities in government, tourism, or customer service roles by leveraging that skill. If you don’t, it’s usually not a barrier to employment in the private sector except in the specific contexts mentioned. This is quite a contrast to Quebec, where not speaking French can be a significant barrier in many fields due to both legal and cultural factors.

Sector-by-Sector Differences in Quebec

Within Quebec, the need for French (and/or English) at work can vary by industry and sector. Let’s examine how French language requirements play out in different job sectors:

Technology and Multinational Corporations (Tech Sector)

The technology sector in Quebec, particularly in Montreal, is booming with global companies and startups. This sector tends to be more linguistically flexible internally, but it’s still subject to Quebec’s language laws. Many tech companies in Montreal have a culturally diverse, international workforce – you might walk into an IT firm and hear employees speaking French, English, Spanish, Arabic, or Mandarin at their desks. English often emerges as a common working language in these companies, given that much of the tech world operates in English (programming languages, technical documentation, communication with U.S. clients or head offices, etc.). In fact, Montreal is known for its high rate of bilingualism and multilingualism. A Statistics Canada study highlighted that among workers in the Montreal area, 80% are at least bilingual (69% fluent in both French and English) – the highest rate of bilingual workers among Canada’s big cities. This means in most tech workplaces, a large majority of staff can switch between French and English.

However, legal requirements still apply: all software or tools used by employees should have French versions if available, and all formal employee communication (HR policies, contracts, etc.) must be in French. So a video game studio from the US, for example, might conduct daily scrum meetings in English, but it needs to give its employee handbook and training manuals in French, and ensure any internal memo to all staff is at least translated to French. If the code repository interface or an internal app has a French version, the company should provide it or enable it. Also, if a tech company is hiring, it cannot simply state “English required” unless it can justify that French alone isn’t enough for the role – maybe because the developer will liaise with anglophone teams abroad daily (which could be a valid reason if documented). Under Bill 96, even multinational tech firms are expected to “promote and encourage the use of French in internal communications” and not list English as a requirement for jobs unless absolutely necessary.

In practice, many tech companies strike a balance: internal team conversations may happen in whatever language is easiest for participants, but official meetings might default to French if even one attendee is more comfortable in French (or be bilingual). It’s common in Montreal tech offices to hear a meeting start in French, switch to English to accommodate someone, and then back to French – Montrealers are adept at this switching. Some companies adopt English as the primary working language internally (especially if founded by non-francophones or with many international staff), but even those must ensure that any employee who wishes to work in French is not prevented from doing so. Culturally, the tech sector is often seen as more anglophone-friendly in Montreal, which has drawn many non-French-speaking Canadians and foreigners to these jobs. You can find anglophone software developers or game designers living in Montreal who function mostly in English at work. The Quebec government has sometimes expressed concern about this trend, fearing English might overtake French in professional settings if not kept in check. This was one motivator for Bill 96 – to remind even the global companies that French must not be sidelined. For employees, this means if you don’t speak French, you could still get a job in a Montreal tech company, but you may hit a ceiling or face challenges: outside the workplace, life in French will catch up with you, and even at work you might miss out on conversations or networking if you can’t speak the majority’s language. Moreover, your employer might push you to learn French over time, and certainly all your official documents will be in French.

Case example: Ubisoft, a major video game company in Montreal, has a workforce from around the world. English is often the lingua franca in day-to-day technical collaboration (because the games are for a global market and teams are international). But Ubisoft must comply with OQLF rules: software like email clients or development tools are provided in French versions where possible; signage in the office is in French; if an employee requests it, they can receive communications or even their workstation’s operating system in French. Ubisoft Montreal also offers free French classes to employees who need them (as do many multinationals in the city). This kind of accommodation is typical – companies want to attract top talent from anywhere, but they know to operate in Quebec they have to respect the language environment. For an employee, it means you can survive with English initially in such workplaces, but there’s support and expectation to integrate linguistically.

To sum up, the tech sector in Quebec is relatively bilingual or multilingual in practice, but French remains a legal necessity for documentation and an important part of corporate compliance. Newcomers in tech should still invest in French, since it will help in subtle ways – from understanding the lunchroom chatter to complying with unexpected regulations (e.g., a francization committee meeting) to expanding your job opportunities into roles that deal more with local clients or government.

Retail, Hospitality and Customer Service

In retail stores, restaurants, hotels, and other customer-facing sectors, French language requirements are very visible and strictly enforced in Quebec. These are the environments where language is part of the customer experience, and Quebec law and culture demand that customers be served in French first.

If you work in a shop or restaurant in Quebec, you’re generally expected to greet customers in French – the classic “Bonjour!” when someone walks in the door. In bilingual Montreal, many staff follow “Bonjour” with an immediate “Hi” (the famous “Bonjour-Hi” greeting) to signal they can switch to English if needed. This has actually been a point of political discussion: as of 2024, about 11.9% of Montreal businesses use the bilingual “Bonjour-Hi” greeting, a sharp rise from a decade earlier. Meanwhile, those greeting customers solely with “Bonjour” had dropped to about 71%. Some Quebec officials worry that bilingual greetings might encourage customers to default to English, and there have been (non-binding) political resolutions suggesting businesses stick to just “Bonjour.” In fact, Montreal’s mayor in 2024 called on businesses to offer employees more French language training so that “Bonjour” can remain the default and employees feel confident continuing in French. This highlights that cultural expectation: even though saying “Bonjour-Hi” is well-meaning bilingual customer service, many Québécois prefer an emphasis on French in public interactions. Still, in practice, a bilingual greeting is often used in downtown Montreal’s shops, reflecting the city’s mixed population.

Legally speaking, any Quebec customer has the right to be informed and served in French. So, if you work in retail/hospitality, your employer must ensure that you (or a colleague present) can handle French transactions at all times. Many job postings in Montreal for retail or waiter jobs will say “bilingual required” because the business expects both local francophone and anglophone/tourist clientele. How does that jibe with the law about not requiring another language? Typically, for a customer service role in central Montreal, an employer can justify requiring English (in addition to French) as necessary for the duties – e.g., a downtown boutique will legitimately get many English-speaking tourists, so speaking some English is a bona fide requirement. They would still write the job posting in French and include a line like “Doit parler français et anglais – clientèle touristique anglophone” (must speak French and English due to anglophone tourist clientele), thereby giving the justification and complying with Bill 96’s posting rules.

All signage and labeling in a store must be French or predominantly French. Product labels must have French (which is often handled by suppliers), and things like menus or information pamphlets must be in French. There have been famous incidents: one called “Pastagate” (2013) where an Italian restaurant got a warning from OQLF because its menu listed “pasta” (an Italian word understood in both French and English) instead of the French word pâtes. The incident caused public ridicule and embarrassment for the OQLF’s overzealousness, and the complaint was dropped, but it served as a lesson to the OQLF to pick its battles – and to restaurateurs that it’s safest to have French on the menu for everything, even loanwords. More recently, fines have been issued to businesses like coffee chains and small shops for not having French on outdoor signs or for having English-only social media ads, etc.. So retail managers are quite vigilant now.

From an employee perspective, if you’re working in Quebec’s service industry, you should be prepared to use French most of the time. Even if you’re bilingual, you’ll usually start in French and then switch to English only if the customer signals they prefer English. Many workers use “Bonjour-Hi” and then continue in whichever language the customer responds in. If you only speak English and not French, your employment options in Quebec’s customer service sector are limited to very tourist-oriented jobs or specific anglophone-enclave businesses – and even then, it’s tricky. For example, in the predominantly English-speaking West Island of Montreal or certain parts of downtown, you might find businesses where English is commonly used, but any of those businesses could still get a francophone customer at any time, and legally they must be ready to serve them in French. Employers know this and therefore will almost always prefer hiring someone at least functionally bilingual over someone who speaks only English. On the other hand, speaking only French is usually fine in those jobs (unless the business explicitly needs you to communicate with an English-only clientele as well).

In hospitality (hotels, tourism), bilingualism is extremely valued. Montreal hotels often require staff to know a third language on top of English and French (Spanish, Mandarin, etc.) – but French remains mandatory. A hotel receptionist in Quebec City who spoke perfect English but no French would be a non-starter; reverse that (perfect French, no English) and they could manage, though in high-end hotels English is expected too.

One more note: tipping culture and customer relations in Quebec can also have a language dimension. There have been anecdotes of anglophone waitstaff in Montreal being chided by locals for not being able to take orders in French. While many Montrealers are bilingual and accommodating, making the effort to address people in French is seen as polite and professional. For newcomers working in this sector, investing in learning key French phrases and improving fluency directly impacts job performance and often, tips (a happy customer in their own language is a generous customer!).

Public Sector and Government Services

Working in the public sector in Quebec (this includes provincial government, municipal government, health and social services, education, etc.) generally comes with the strictest French language requirements of all. The Quebec government conducts its internal business almost entirely in French. Legally, civil service positions in Quebec usually require French proficiency. When you apply for a job at a Quebec ministry or a city hall, you’ll typically have to demonstrate strong French abilities. Each institution can set the level of French needed for a job, often subject to OQLF approval. For example, to be hired as an agent at Revenu Québec (the provincial revenue agency), you must be fluent in French since you’ll be working in French and serving citizens who expect service in French. Provincial public servants do not have a “right” to work in English analogous to the federal employees’ rights – the language of work is French, period.

There are exceptions for certain institutions: Some municipalities in Quebec have bilingual status (e.g., Westmount, Town of Mont-Royal, etc., typically where there’s a large anglophone population). Also, certain health and social service institutions are designated as bilingual to serve the English-speaking community (for instance, the McGill University Health Centre hospitals in Montreal, or certain nursing homes). In those, French isn’t always required to get a job or promotion – they can hire staff who speak only English if the role is oriented to serving English clientele. English-language public school boards are another example: a teacher or staffer at an English school board obviously needs English; they are encouraged to know French too, but the law allows English school boards to operate in English internally for the most part. Still, even in bilingual-designated institutions, a lot of coworkers will be francophone or bilingual, so it helps to speak French for daily life and workplace cohesion.

The education sector in Quebec (apart from English schools/universities) is entirely French. If you plan to teach in Quebec (in French schools or CEGEPs, or at the University of Quebec network), you must have a strong command of French. Even at English-language universities like McGill or Concordia, administrative staff often need some French because of dealings with the government or general public, and internal documentation might need to be bilingual.

In law enforcement, consider the example of the Montreal Police (SPVM): Historically, Montreal being a very bilingual city, police officers were expected to know both languages to serve the public. Recently, there have been discussions and policy adjustments about relaxing the immediate bilingual requirement for new officers (focusing on French and then teaching English later) to widen the recruitment pool of francophone officers. But the expectation remains that officers will become bilingual to effectively police all communities. Similarly, firefighters and paramedics in Montreal benefit from bilingual ability, though the primary working language in the station might be French.

For the federal public service roles located in Quebec, as covered earlier, many are bilingual positions, especially if they interact with the public. So in places like Montreal, even to work as a Service Canada clerk (federal) or a border services officer at the airport, you likely need to be bilingual. Conversely, in Gatineau (the Quebec side of Ottawa), a lot of federal jobs are French-essential or bilingual.

Career advancement in the public sector also ties into language. In Quebec’s provincial public service, an anglophone with limited French would find it nearly impossible to advance, because meetings, communications, and politics are in French. In the federal realm, an anglophone in Montreal might be okay at entry level if their French is moderate, but to advance they’d need to polish up to meet the bilingual requirements for management.

To illustrate, a Quebec healthcare worker: If you work as a nurse in a Montreal hospital that isn’t officially bilingual, you must chart and communicate in French predominantly. But you’ll also likely deal with patients in English regularly, so hospitals value bilingual staff and often provide language training. The OQLF keeps a list of bilingual designated institutions in health; as of 2025, about 50 hospitals/clinics have that status, meaning they are committed (and required) to offer all services in English as well as French. Working at one of those, you might get away with being less than perfect in French because the institution’s mission includes serving anglophones. Yet, documentation and colleagues’ communication will still involve a lot of French.

In sum, the public sector in Quebec is predominantly a French-first environment with some room for English depending on the institution. If you aim to work in Quebec’s government or public services, you should prioritize achieving a high level of French. Even for anglophones born in Quebec, there’s often a conscious effort to attain strong French skills to access these stable, well-paying public jobs. For newcomers, there are bridging programs and language exams one must pass (e.g., an internationally trained nurse might have to pass a French proficiency exam to get licensed in Quebec, since professionals must demonstrate knowledge of French). Quebec values French in its public sphere not just as a policy but as a statement of identity.

The Business World: Commerce, Finance, and Others

It’s also worth briefly noting other sectors like finance, manufacturing, and trades. In finance and banking in Montreal, French is essential for client relations (a bank teller, financial advisor, etc., will use mostly French, switching to English for some clients). The internal working language of big banks might be more bilingual because head offices often are in Toronto, but Quebec branches operate in French primarily. Still, corporate jobs in finance in Montreal often require bilingual reports and communication to serve national markets. If you’re an analyst at a Montreal investment firm, you might write research in English for a wider audience but discuss it in French with local colleagues – or vice versa. Professional services (law, consulting, accounting) in Quebec similarly demand high French for local practice – contracts and court pleadings must be in French (Bill 96 even requires certified French translations of English court pleadings now) – but professionals often need English to deal with out-of-province clients or international work. These sectors usually expect bilingualism as a given for hiring, because they straddle local and global environments.

Manufacturing and skilled trades: On a factory floor or construction site in Quebec, the language is overwhelmingly French (outside some pockets of Montreal or the Eastern Townships). Workers communicate in French; safety trainings and manuals must be in French. An anglophone tradesperson might get by in an English enclave or if hired by an anglophone-run company, but any formal certification or trades exam will be in French.

Thus, across sectors, the variance often comes down to how much the job engages with the international sphere or the local public. The more local-public facing, the more French is paramount. The more global-facing (as in many tech or multinational corporate roles), the more English creeps in – but even then, the scaffolding of legal obligations keeps French present at least in formalities and often in day-to-day office life.

Cultural Expectations and Workplace Dynamics

Beyond the black-and-white of laws, there’s a cultural layer to language at work in Quebec (and to a lesser extent in other parts of Canada). Language is a sensitive, identity-charged topic in Quebec. Francophone Quebecers generally appreciate when colleagues and newcomers show willingness to communicate in French. Even if your French isn’t perfect, making an effort goes a long way in building trust and camaraderie. Many francophones are bilingual and will switch to English to help you out – but they notice and value when you try in French.

Workplace culture in Quebec might involve small things like using French greetings (“Bonjour” in the morning to everyone in the office), writing emails with a polite French sign-off, or attending after-work social events where conversations default to French. There’s often an unspoken expectation that the common language in group settings will be French. An anglophone who continuously insists on English in group discussions may be seen as not being a team player or as disrespecting the majority, even if no one says it outright. Conversely, colleagues will be supportive if they know you’re learning; you might find they’ll correct you gently or teach you office jargon. Quebec workplaces can be quite friendly about this – there’s a pride in helping someone integrate into French.

“Bonjour-Hi” in the workplace: The phrase is emblematic of Montreal’s bilingual reality, but also of the balancing act. In a team meeting, someone might start presenting in French, then add an aside “I’ll switch to English for our colleague who isn’t comfortable in French – hope that’s okay with everyone: so, basically…” That accommodation happens often. However, with Bill 96, there is a bit more pressure on companies to not make such switches routine. Don’t be surprised if some meetings or written materials that used to be bilingual switch to French-only (with maybe a summary in English) as organizations try to align with the spirit of the law. Francophone employees, for their part, have gained confidence to assert their preference to work in French. Some have reported feeling more at ease saying, “Actually, I’d prefer if we do this meeting in French,” whereas before they might have just gone along in English. The law has to some extent empowered francophones in workplaces to ask for French accommodations that they might have hesitated to demand earlier.

In the rest of Canada, cultural expectations differ. Outside Quebec, a francophone working in, say, Alberta knows that the workplace will be English-dominated. They might speak French with a fellow francophone at lunch, but all official business is in English. They typically won’t expect accommodations to work in French (unless they’re in a federal office or such a context). They might appreciate an employer who values their bilingualism and perhaps occasionally utilize their French for a francophone client, but English is the cultural norm.

In New Brunswick, cultural expectations are unique – both English and French workers expect a bilingual environment. It’s not uncommon in some New Brunswick government offices to hear a mix of both languages, and people switch easily. The idea of saying a sentence half in French, half in English (franglais) is more accepted in informal talk, because so many people are fluently bilingual. But formal settings still require careful use of each language properly.

One should also note office humor and socializing: In Quebec, humor is often very tied to language. Quebec French has a lot of slang and nuances; if you’re not familiar, you might miss the joke or the cultural reference. Integrating involves learning these little things – from the tu vs. vous (informal vs. formal “you”) usage among colleagues, to common Quebec idioms. Colleagues will likely invite you to join them in French conversations; being able to at least partly join is key to not feeling isolated. Many newcomers recount that the real breakthrough at work came when they could finally small-talk in French by the coffee machine – that’s when they felt truly part of the team.

Resistance and openness: There can be both. Some anglophone Quebecers (especially older generations in certain communities) have harbored resentment towards Bill 101 and prefer to work in English. Conversely, some hardcore francophones might be impatient if an anglophone colleague always defaults to English. But broadly, especially among younger generations, there is a lot of bilingual coexistence and openness. Montreal in particular prides itself on being a cosmopolitan bilingual city. It’s not unusual to have a team meeting where half the participants are francophones who grew up watching Hollywood movies in English, and the other half are anglophones who went through French immersion school – so everyone’s kind of bilingual and switches language unconsciously. That often works smoothly. The legal framework simply ensures that, at the end of the day, French doesn’t lose its place as the common language in Quebec’s public sphere.

Language and career networking: Being part of professional networks in Quebec often requires French. For example, many industry conferences, chamber of commerce events, or training workshops in Montreal will be in French (or bilingual). If you attend only English-language networking events, you might miss out on a big portion of the local network. Conversely, joining francophone professional associations can boost your career prospects. Quebec also has its own professional designations and regulatory bodies (for law, medicine, engineering, etc.) that operate in French, so engaging with them means navigating French documentation and meetings.

In conclusion, understanding cultural expectations means recognizing that language is more than a tool in Quebec – it’s part of respect and relationships. Adapting to that culture, even as laws tighten or change, will make one’s work life more rewarding.

Tips and Resources for Newcomers to Improve Workplace French

If you’re new to Quebec or aiming to work here (or anywhere that French might be needed), improving your French is one of the best investments in your career. Given the importance of French at work in Quebec, the provincial government and various organizations offer a wealth of resources for language training and integration. Here are some practical steps and resources:

Take Advantage of Free Government French Courses: The Government of Quebec offers free French classes to all adult immigrants and newcomers in the province. This includes full-time and part-time courses, with flexible schedules to accommodate work. In many cases, there is even financial assistance – for example, a stipend (around CAD $200 per week) for full-time attendees, to offset living costs while you study. Check out programs by the Ministry of Immigration, Francisation and Integration (MIFI), often branded under Francisation Québec. They provide classes from beginner up to advanced business French. There’s also an online platform called Francisation en ligne (FEL) for self-paced learning before or after you arrive.

Work-Integrated Language Training: Some programs specifically target French learning on the job. For instance, there are courses that simulate workplace scenarios – writing emails, chatting with colleagues, giving presentations in French, etc. According to a Concordia University study, work-integrated French training can significantly help overcome employment barriers for English-speakers in Quebec. Ask your employer or look for community programs that provide French coaching tailored to your profession (e.g. French for IT, French for healthcare). Large employers sometimes partner with language schools to offer in-house French classes during lunchtime or after work.

Language Partner or Mentor: Pairing up with a francophone colleague or friend for conversation practice can accelerate your learning. Quebecois are generally pleased when someone is trying to learn French and many will gladly help you practice. You could propose a deal with a coworker: you’ll practice French with them if they want to practice English with you (though trust me, you need the French more if you plan to stay in Quebec!). This can be done informally or through organized programs like language exchange meetups available in Montreal and other cities.

Utilize Daily Interactions: The workplace itself can be a classroom. Don’t shy away from using your budding French on the job. Start emails in French (you can use tools like Antidote or even DeepL/Google Translate to help formulate sentences, but try to learn from them). Attend the French lunch & learn sessions. When someone says something in French you don’t catch, politely ask “Pourriez-vous répéter plus lentement?” (“Could you repeat more slowly?”) or ask a colleague afterwards to explain a word. Most colleagues will be supportive and perhaps even switch to simpler French to help you along. Over time, immersion does wonders.

Embrace Quebec Culture: Improving language is not just grammar and vocab, it’s also cultural literacy. Watch popular Quebec TV shows or listen to local radio (e.g., tune into Radio-Canada or TVA news, watch a show like “Tout le monde en parle” or a comedy series). This trains your ear to the Quebec accent and gives you conversation fodder with colleagues. Music is another great way – Quebec has a rich music scene (try listening to francophone artists like Cœur de pirate, Les Cowboys Fringants, or classics like Céline Dion’s French albums). If you like sports, follow the Montreal Canadiens hockey games with French commentary. Not only will this improve your comprehension, but it also shows coworkers you’re interested in “their” culture, which earns goodwill.

Use Technology and Apps: Complement classes with apps like Duolingo, Babbel, or Memrise focusing on French. There are even Quebec-specific French learning apps that teach local expressions. While apps alone won’t make you fluent, they’re good for building vocabulary. Another tip: change your phone and computer interface to French – this way you learn tech and office terms in French (useful when those IT tools at work come in French!).

Professional French Tests and Certifications: If you’re in a profession that requires licensing in Quebec (engineering, nursing, etc.), you might need to pass a French language exam. The OQLF administers exams for certain professions to certify language ability. There’s also the TEF (Test d’Évaluation de Français) or TSF that immigrants take for Canadian immigration or Quebec certification. Even if not required, getting a certification can be a motivator and a resume booster. For example, obtaining a diploma in French for profession (Diplôme de français professionnel) could show employers you have a certain level of workplace French.

Learn Workplace Jargon: Every industry has its jargon, and often the English terms are used in Quebec even in French sentences (e.g., “le software”, “le marketing”). But many also have French equivalents. Once you know where you’ll be working, make an effort to learn the French terminology of that field. If you’re in accounting, learn terms like bilan (balance sheet), états financiers (financial statements), etc. The OQLF website has a great terminology section where you can lookup standard French terms for various technical words. Using the proper French terms at work (rather than anglicisms) will earn you respect for professionalism. Co-workers might even pick up and use those terms more because of you.

Practice, Patience, and Attitude: It takes time to become confident in a new language. Don’t fear mistakes – they are part of the process. Quebecers will not mock you for mistakes; on the contrary, they’ll appreciate the effort. A sense of humor helps: if you accidentally said something embarrassing in French (very possible with false friends!), laugh it off – colleagues will find it endearing and it becomes an ice-breaker. Set small goals: this week I’ll try to handle all my customer greetings in French without switching; next month I’ll attempt a brief presentation in French at the team meeting. Celebrate progress – for instance, the day you finally managed a phone call with a client entirely in French, or when you wrote an email without relying on translation tools.

The Quebec French language commissioner, Benoît Dubreuil, noted that current programs have to improve to offer newcomers a realistic path to integrate into workplaces in French. He pointed out issues like high dropout rates in francization courses when people start from zero French. His advice aligns with the tips above: companies should recruit people who aren’t at “level 0” French or invest in pre-arrival French training, because once someone starts working full-time, it’s hard to find the time and energy to learn a language from scratch. This is a sobering point – if you plan to move to Quebec for work, start learning French as early as possible, even before arriving. And if you’re already there and working, push your employer to allow time for language training. Dubreuil even recommended employers be obliged to give workers more time during work hours to attend French courses – perhaps something you can lobby for in your workplace.

Finally, remember that learning French is not just a work skill, but a gateway to fully experiencing Quebec society. It will enrich your social life, allow you to enjoy local media, and make you feel at home. Thousands of newcomers have successfully become bilingual and thrive in Quebec’s job market – you can too. The province truly offers a lot of support because it has a vested interest in seeing you succeed in French. Take that help, put in the effort, and you’ll find that speaking French at work becomes less a requirement and more a rewarding reality of your Canadian experience.

Real-World Examples and Case Studies

To ground all this information, let’s recap a few real-world scenarios that illustrate French language requirements at work in action:

The Job Candidate Who Fought for French: In 2024, a man in Quebec applied for a job and was asked by the employer to submit his CV in English and even do the interview in Korean (because the company’s manager didn’t speak French). The candidate felt this was unfair – after all, the job was in Quebec. He invoked the new provisions of Bill 96 and filed a complaint. The Labour Tribunal ruled in his favor, stating the employer failed to prove that English or Korean were truly necessary for the job and hadn’t taken all reasonable steps to avoid imposing those language requirements. This case was precedent-setting; it put employers on notice that the right to work in French is enforceable. The outcome likely will be the company has to pay damages or even reconsider its hiring practices. For job seekers, it was a powerful message: you can stand up if you feel an employer is unnecessarily demanding another language – the law is on your side in Quebec.

OQLF Crackdown on Businesses: The Office québécois de la langue française conducts investigations and follows up on complaints. A notable example was the Kernels Popcorn franchise fine in 2023. A Montreal location of this Canadian popcorn chain had a website with no French option – completely English. A complaint was filed in 2021; OQLF tried to get the company to fix it, but got no response. Eventually, the matter was escalated to the province’s prosecutors and the company pleaded guilty to an offense under the Charter of the French Language (section 52). They were fined $2,500 and promptly put up a French version of the site. Around the same time, other businesses were fined for infractions like missing French on product packaging or having exterior English signs without sufficient French. While these fines aren’t enormous for businesses, the reputational hit (nobody likes being called out by the “language police” in media) and the hassle of legal proceedings are strong deterrents. It shows that compliance isn’t optional, and even national chains must adapt their operations (e.g., ensuring their e-commerce or marketing is bilingual) when operating in Quebec.

Francization Success and Challenges: A positive example is of companies that proactively embraced francization. Some years ago, big retailers like Walmart and Costco, when expanding in Quebec, made it a point to have French signage, French training for staff, etc., even if head office was in the U.S. This helped them avoid major run-ins with OQLF. On the flip side, the French Language Commissioner’s 2024 report flagged that many smaller employers struggle with implementing effective French training at work. Temporary foreign workers and new immigrants often enroll in language courses, but completion rates are an issue (23% dropout as cited). The commissioner recommended standardized workplace French courses and giving employees more paid time to attend them. As a case in point, a manufacturing company might hire a group of allophone (neither English nor French as first language) workers due to labor shortages. They offer a 1-hour/week French class on-site. But workers are tired from shifts, some miss classes, and progress is slow – leading to continued communication problems on the floor and safety issues if instructions are misunderstood. The report suggests that unless such companies either hire people with some pre-existing French or dedicate more resources to training, both the employee and the employer will be frustrated. It’s a call to action in the real world: invest in language or face integration failures.

The “Bonjour-Hi” Debate in Retail: Culturally, an example was when the Quebec National Assembly in 2017 passed a unanimous (but symbolic) resolution calling on store clerks to stick to “Bonjour” and drop the “Hi”. While it had no legal force, it did cause quite a stir. Some downtown Montreal retailers were nervous – should they change their greeting? The Premier at the time had to clarify that nobody would be fined for saying “Hi” and that it was just an encouragement to valorize French. Over the next few years, surveys by OQLF noted that bilingual greetings actually increased, which some took as Montreal merchants quietly rebuffing the politicians’ wish. By 2024, seeing the significant uptick in “Bonjour-Hi”, Montreal’s mayor instead took a constructive approach: rather than scold businesses, she suggested providing better French language support to employees so that they feel comfortable using just “Bonjour”. The pragmatic understanding is that many employees revert to a bilingual greeting or English because they lack confidence in their French if the conversation continues. So, the real-world solution loops back to training and integration.

Federal Workplace Scenario: Consider a federal government office in Gatineau (Quebec) versus one in Winnipeg (Manitoba). In Gatineau (which is part of the NCR, bilingual region), a team may have anglophones and francophones. Meetings often alternate language or provide materials in both; employees are allowed to draft documents in either language. One anglophone employee might speak in English in a meeting and the francophone colleague responds in French – and that’s perfectly fine and common. That employee, if they aspire to promotion, will likely take French courses to improve their French so they can chair meetings in French in the future. Meanwhile, in Winnipeg’s federal office (non-bilingual region), internal work is almost entirely in English. A francophone employee there might not get to use French much except when serving a French-speaking member of public or talking to a Quebec colleague by phone. But under the OLA, if that francophone employee transfers to a bilingual region, they can then exercise their language of work rights. There have been cases (and complaints) where employees outside Quebec said their opportunities for advancement were limited by not being bilingual, or where in bilingual offices some felt the culture was still dominated by one language. The Commissioner of Official Languages often cites such cases urging federal departments to better implement true bilingual workplaces.

Each of these scenarios underscores aspects of what we’ve discussed: the legal muscle behind French in Quebec, the practical challenges, and the cultural balancing act. They highlight that while laws set the stage, the day-to-day play involves real people and businesses adapting in varied ways.

Conclusion: French language requirements at work in Canada form a mosaic – with Quebec’s strong colors dominating the picture, federal bilingualism providing a national frame, and other provinces adding lighter shades of bilingual practice. For anyone working in Canada, and especially in Quebec, understanding this linguistic context is crucial. Legally, if you’re an employer in Quebec, compliance with French language laws isn’t just a formality but a core business responsibility. If you’re an employee (or job seeker), knowing your language rights (and limits) helps you navigate the job market – you can insist on French in Quebec, or see the added value of French skills elsewhere. Culturally, embracing bilingualism (or in Quebec’s case, embracing French with an open-minded bilingual twist) will enrich your career and personal life.

Canada often advertises itself as a bilingual country, but the reality is nuanced. It’s more accurate to say Canada is a country of bilingual institutions and regions, and of two major linguistic communities coexisting. Workplaces are where these communities interact daily. In Quebec, that interaction is carefully guided to protect the francophone character, while across the rest of Canada it’s more organic and market-driven.

Ultimately, language is about inclusion. The goal of these requirements and initiatives is to ensure francophones can live and work in their language without barrier, while anglophones and allophones can also participate in society. For newcomers, it might seem daunting to master French, but the support is there and the effort is profoundly worthwhile – professionally and personally. The road to bilingualism can be challenging, but at the end you’ll find not only better job prospects but a deeper connection to the community you live in.

Whether saying Bonjour, Hi, or both, the message is: in Canada’s workplaces, language matters. And navigating those requirements is part of the job – one that this guide, hopefully, has made a bit clearer.

Sources:

Quebec Charter of the French Language & Bill 96 (2022) : Key provisions for language of work.

OQLF and Quebec government announcements : Language requirements for job postings, francization thresholds.

Éducaloi legal information : Rights of workers to work in French, obligations for documentation.

CityNews Montreal : Case of a worker winning right to interview in French; French Language Commissioner’s report on newcomer francization.

Global News : OQLF studies and fines: companies requiring English skills; increase in “Bonjour-Hi” greetings and political responses; business fined for not having French on website.

Wikimedia Commons (Tony Webster photo) : Bilingual stop sign in Montreal illustrating dual-language signage.

Official Languages Act (federal) : provisions for language of work and bilingual positions in federal service.

Data on bilingualism in federal jobs : ~42% positions bilingual as of 2022.

New Brunswick Official Languages Act : equal status of English and French, requirements for services province-wide.

Ontario French Language Services Act ; guarantees public right to provincial services in French in designated areas.

OXO Innovation article (2025) : Montreal’s multilingual workforce stats (80% bilingual) and emphasis on French in business after Bill 96.